Back in 1999, in an effort to modernise the systems that sit below our national postal service, The Post Office announced the roll out of a brand new piece of accounting software called Horizon.

Unless you have been living under a rock for the past couple of weeks, you will know exactly what happened next.

Postmasters all around the country, almost immediately, begin reporting irregularities. They notice that the system occasionally and erroneously reports large shortfalls on their accounts. They report this issue to the Post Office in good faith.

But rather than look under the bonnet of their whizzbang new system, the Post Office insist that human error is to blame. When individual postmasters, rightly, refuse to make up shortfalls that the system has invented - the Post Office claims that they are on the take.

Over a hundred prosecutions follow over the course of the next three years. Lives are ruined. Truly tragic consequences follow.

What has been until recently a disgracefully niche story, covered diligently and persistently by only a handful of journalists, has all of a sudden come screaming into the public consciousness as a result of the recent ITV drama Mr Bates v The Post Office.

If you haven’t seen it yet, you really must. The experience of watching it can be best described as simultaneously heart breaking, and enraging.

But it has had the desired effect. A fire that was beginning to smoulder and crackle into life after years of campaigning, just had a can of petrol chucked onto it.

In the past couple of weeks the Prime Minister has described the affair as “one of the greatest miscarriages of justice in our nation’s history”. Public honours have been returned. Emergency legislation to clear the names of those wrongly convicted is being drawn up. Criminal action against those responsible for the cover up appears likely.

The campaign to right the wrongs of the past two and a half decades now, finally, seemingly has real momentum. And momentum can be one of the most powerful forces in the world.

The power of momentum shows up in a couple of ways when we think about investing. The first and most obvious way is when we think about compounding returns*. Growth begets growth, and like a snowball rolling down a hill seemingly moderate and uninspiring investment returns will compound into something extraordinary, if we let them.

Academic research also tells us of the power of momentum when it comes to the performance of stock prices. Put simply - the data shows that stocks that have been going up recently tend to keep going up, and stocks that have been going down tend to keep going down.

In my view the best explanation for this comes from human nature.

Good news about a company begets optimism, and optimism results in two things. One - a higher valuation for the company’s stock; and two - a greater willingness on the part of investors to look past any information which could be construed as negative.

This becomes a self-reinforcing pattern - if investors are prepared to look past the risks inherent within an individual business, and only focus on the positives, then the share price is only likely to trend in one direction.

This momentum then feeds on itself to create a viral narrative, which results in a powerful and pervasive “fear of missing out” within those not lucky enough to be in the stock.

Ahem.

Nothing in life is more infuriating than seeing your neighbour getting rich easily. So more and more people spin whatever story to themselves that they can in order to justify getting in on whatever the latest hot craze is.

“The world isn’t driven by greed, it’s driven by envy”

Charlie Munger

This process, dear reader, is how bubbles form. And we all know that when bubbles pop it tends not to be pretty.

There is no such thing as a silver bullet when it comes to investing. Investing based on momentum is a high maintenance strategy, not to mention highly volatile and incredibly stressful.

Nonetheless, the data shows us that taking a systematic approach to investing using momentum has worked fairly consistently over the couple of hundreds of years of data that we have available.

Despite all of the advancements that we have made as a species during that time, our nature hasn’t changed. It never will.

Before any of us had ever heard about the stock market, we would have heard the phrase “buy low, sell high”. This approach makes sense to us because it is entirely intuitive.

Therefore we can naturally feel uncomfortable investing when markets are at all-time highs, as many equity markets are today. By buying high, it feels like ours is the “dumb money”. The last man in.

However the data shows us that investing into globally diversified stock markets at all-time highs is nothing to be frightened of.

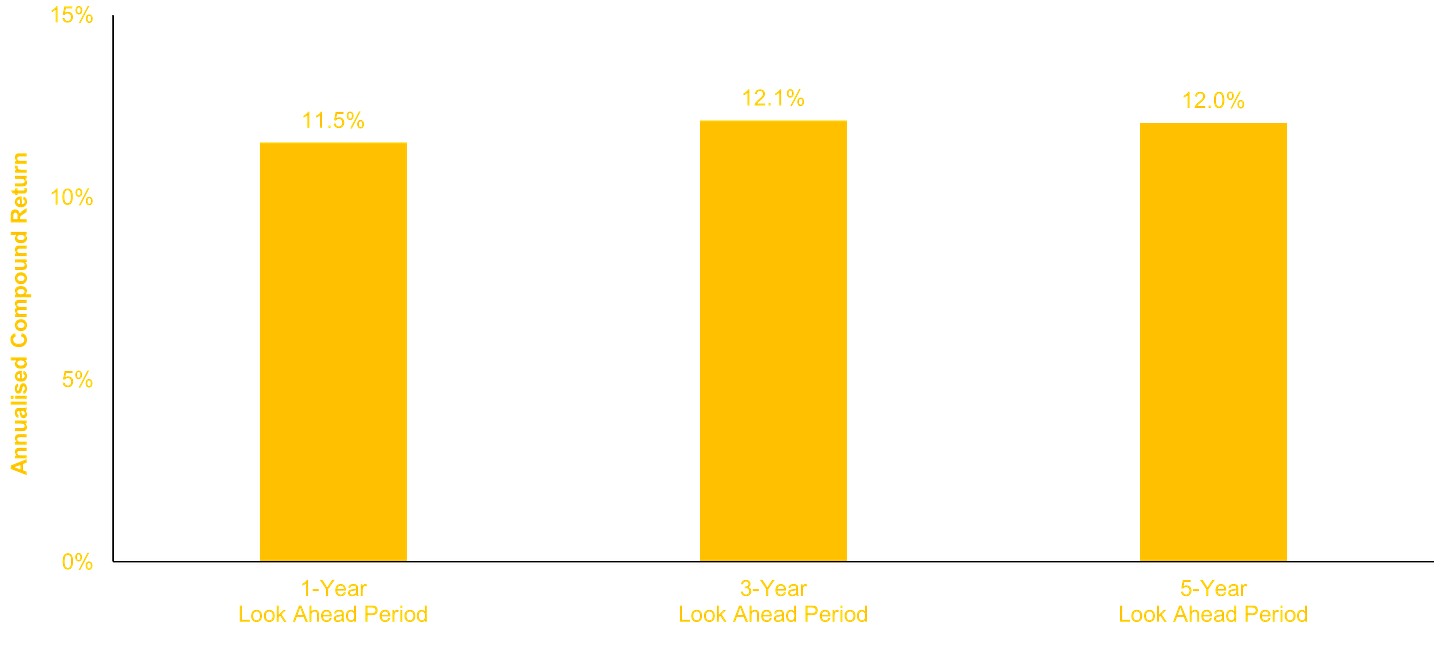

The below chart shows the average annualised one, three and five year returns for the MSCI World index, in Sterling terms, following all time highs for that index (which is a decent proxy for the global stock market).

Source: MSCI, Dimensional Fund Advisors. Using data from January 1970 to December 2022.

Whether due to momentum or not, all time highs for the stock market have been a pretty good time to invest on average.

The reason that taking a “buy low, sell high” mindset to investing in the stock market as a whole is dangerous, is that the long term trend for capitalism is up and to the right.

Put in a slightly different way, every asset price bubble has been accompanied by all time highs for the stock market - but not every all time high for the stock market is accompanied by a bubble. There is no way of telling which is which in real-time.

“Buy low, sell high” implies that there is a time when you shouldn’t be buying, when hundreds of years of market history tell us that we should be buying financial assets at every opportunity that we get.

We should be buying when its sunny, and buying when its raining. Buying in January and buying in June. Buying on every day of the week, and twice on Sundays.

Buying at all-time highs, and backing the van up to buy when stocks are on sale.

Have a great weekend.

None of the above constitutes investment advice, and as ever, past performance is not indicative of future returns.

*Time for another below the line explainer. If you haven’t heard of compound returns before, I promise it is a pretty straightforward concept to get your head around. Compound returns simply refer to returns earned, not only on the money that you originally invest, but also on the growth that you receive on that money over time.

To take an example, let’s say that you invest £1,000, and you earn a 5% annual return. At the end of year one you have £1,050.

And let’s say that in year two you earn another 5%. At the end of year two you have £1,102.50, not £1,100.

Reason being that in that second year you are not just earning a 5% return on the principal capital that you invested on day one, but you are also earning a return on the growth that you saw during the first year. Growth on growth if you like.

Compounding returns are the reason that you only need an average annual return of 7% approximately to earn a return of 100% (or double your money) over a ten year period.

Compounding returns are also the reason that you youngsters out there are in such a good place to earn extraordinary returns during your future years as an investor. Any money that you invest today has so much time to grow, and compound by earning growth on that growth, that you almost can’t help but be a successful investor - provided you invest in something sensible (easy enough) and stay out of your own way (difficult).